Celebrating Science

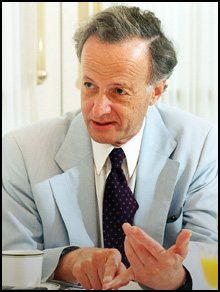

Prof. Dr. John C. Polanyi (Toronto)

It is extraordinarily generous of you to invite an English-speaking expatriate (who left here at the age of four) to address you on this happy occasion. What I say will soon be forgotten, but your generosity will be remembered. It is the most precious of commodities.

The lack of it has caused nations at times to turn inward on themselves, neglecting or actively rejecting the rest of the world. And, as we scientists know, the consequence of that is to destroy the very thing that we wish to preserve; our science, our creative life, ultimately our society.

This Institute exists, I am aware, only because of the generosity of those from the eastern half of this country who, having been deprived, for the second time in a short span of history, of the right to mingle freely with the rest of the world, find themselves now at a disadvantage as researchers. They are being asked to show patience and far-sightedness which is synonymous with generosity in order that the damage done by decades of deprivation can be rectified. This generous spirit is required not just in the field of science but across the nation, as a new Germany emerges.

It is a sobering thought that what Germany is going through today, the world will be faced with tomorrow. Those who have been deprived of their fundamental rights are not only to be found in the former East Germany. I use the term 'rights' broadly, to include the right to freedom of movement and expression, as well as the right to a minimal share in the world's wealth.

The deprived populate much of the globe, and they look at Eastern Germany, as it is today, with profound envy, wondering who will be their West Germany. The real test of our generosity, yours in Germany as well as ours in Canada, has therefore only just begun. If we fail that larger test it will not only be a moral tragedy, but will, I fear, be the signal for war ... .

For something that we in the developed world have distributed in abundance is armaments.

I do not mean to spoil this party by sounding a note of gloom. I am, as you will discover, an optimist. The symbolism of the destruction of the Berlin Wall, not many metres from here, which so inspired and moved the world four years ago, is still the symbol of our times. The raising of absurd and indefensible walls crisscrossing Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, perhaps soon Canada, and increasingly the Soviet Union (to give only a few examples) represents a reversion to outdated thinking. In the world that modern science has created, there is no wall behind which one can hide from hostile weapons, from economic interdependence, or from the anger of the world's poor.

I suppose that there are cynics today who say the wall separating East and West Germany came down for the same reason that other walls are now going up, namely a resurgence of that dangerous force called ethnicity. But the cynics who say that are overlooking a major tide in history; the widespread disgust with walls, and revulsion against treating human beings as cattle to be penned in. Instead there is a strengthened resolve to respect each person and to insist on democratic institutions which empower the individual.

For, along with the wall we should remember another important symbol of our times, half a world away; the image of a single unarmed young man, who by his presence halted an advancing tank in Tiananmen Square, in June of 1989. That was the same month, as you will recall, that the Wall started to be porous; tens of thousands of East Germans crossed to the West by way of Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The wall had been made irrelevant, and the way was open for this Institute to be born.

It is 'born' with a small b, and happily also Born with a capital B. It is, in fact, Max Born who gives me the licence to speak so freely to you today. For he held to the view that scientists were entitled, and indeed obligated, to participate in public debate. He himself did so, through such means as the Pugwash Conferences, articles, and books, among them a book 'Physics and Politicis' from which I shall have occasion to quote.

Science may appear at first sight to draw its strength from the fact that it is removed from politics. And yet an understanding of how the scientific community is organised and how discoveries are made the sort of understanding that comes from involvement in science carries profoundly important messages for politics. Putting it differently, misunderstandings of science have done appalling damage.

I should like to talk a bit today about the nature of science, and the interactions of science with society. I begin by recalling an incident in Max Born's life. This article is accompanied by a picture that hung in Born's study for decades. It was taken in Bristol, England in 1927. It includes as a visitor to Born's study at once recognised reading left to right, Bragg, Eddington, Rutherford, Fowler, & Pierre Langevin. "What a pity", Max Born's visitor remarked, examining the group, "that this young man got into the picture". He pointed to the figure second from the right in the foreground. Max Born was frank enough to exclaim indignantly. "But that's me".

The visitor who made this gaffe may not have realised that Max Born occupied a position in the history of science fully on a par with the other people in this photograph. For the making of great discoveries is not accompanied by signs visible to all; a bell does not ring. Born's case is, in one sense, an extreme example. Almost thirty years passed between his work on the statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics and the award of the Nobel Prize. Yet, today, one can think of few discoveries with wider impact.

This delay in recognition was compounded by a different factor. Science is such a strongly interactive discipline that it is hard even for the participants to recall who contributed what. Ideas are tossed to-and fro from person to person, while being refined and improved at each transition.

Thus Born was involved, as an essential contributor, in the historic 'Drei Männer Papier' of 1926 on matrix mechanics, that carried the names of Born, Heisenberg and Jordan, each a great scientist in their own right. Not only was their work intertwined but the Drei Männer were themselves linked, in what today we would call a network, with a broad group of Männer und Frauen who worked beside one another at institutes such as this, corresponded with one another, attended scientific meetings together, and accompanied one another on long walks. Close links formed, lasted for a few years and then dissolved in favour of new groupings.

The initiative for this subtle process had to come from the individuals involved, since they alone knew what they lacked and what they had to offer. What we see here is the operation of the free market in ideas.

As with the free market in goods, it is the individual entrepreneur who is the best judge of where the opportunities lie. This is because the working scientist is in closest touch with the growing points of the field. Additionally the scientist can be depended on to make the most careful investment of his time, since it is he or she that will be punished in the event of a bad choice of topic.

For science does have (as it is expressed in the world of business) a 'bottom line'. The bottom line is discovery. If, in the estimation of your peers, you fail to make discoveries, sufficiently cheaply and quickly, you are very likely to go bankrupt, once and for all. You will lose your credibility, and with it your research funding. Each scientist in this high-risk enterprise of research is gambling, therfore, with something of unparalleled worth: his career in science. And in science, as in business, it is the risk taker who is the best decision maker.

One would think that this would be an easy argument to make at a time when we are in revolt against the dead hand of bureaucracy, and are so conscious of the virtues of the free market. But in the context of science it is not an easy argument to make. We are in the grip of economic crisis and, in my country at least, we are told by the government that it is irresponsible merely to make discoveries wherever nature allows. We should instead make them in areas of social and economic need.

This appears to be a reasonable request, but there are problems with it. One is that if you do not make discoveries where nature allows, you usually do not make discoveries. And there is nothing so irrelevant as trivial science. The second problem is that any major new departure in the realm of applied science is made possible by not one but several different improvements in fundamental understanding. And it has proved impossible to identify this interlocking group of discoveries in advance of their having been made.

One can, nonetheless, insist that it be done. The consequence of requiring people to do the impossible is that they will pretend to do it. They find themselves competing with one another to write the best science fiction. Unfortunately the people who write the best fiction may not be those who do the best science.

I have been asked to make some reference to my own research interests in the course of these remarks. I welcome this, though with a sense of embarrassment. My work is not on the heroic scale of Berlin science; it merely derives from Berlin science.

Over half a century ago may father, Michael Polanyi, was in Berlin studying a faint yellow glow from the reactions of atomic sodium with halides. He was grappling with a question in fundamental science; how does the rate of chemical reaction in gases compare with the rate at which molecules collide. By comparing the rate of diffusion of atomic sodium through a halide with its rate of reaction, he and his co-workers obtained the remarkable result that reaction took place at more than every gas-kinetic collision. From this was born the notion of 'harpooning'; that is to say of charge-transfer reaction at a distance.

What is less well known is that my father consulted at the same time for the lamp company, Osram. He thought that the intense chemiluminescence might lead to a sort of chemical lamp. In one of his papers there is a photograph of a colleague of his using the sodium plus chlorine reaction as a lamp, and reading the latest news of economic chaos in the Germany of 1929.

Well, my father was wrong about the lamp. His work never provided the basis for any sort of useful luminescence. On the other hand, the collision theory of reaction rates, together with the concept of harpooning, has had so many applications, extending from physics to biology, that nobody cold count them.

This is a prelude to saying that thirty years later, not entirely by chance, I was studying infrared chemiluminescence along with my first graduate student, Ken Cashion, at the University of Toronto. This infrared emission was, apart from being invisible, barely detectable. Unlike my father I was not so stupid as to think at first that it could become a practical light source. But like my father I was wrong. Fueled by the very reaction that I was studying, there emerged the most powerful light source in existence, the chemical or vibrational laser. Though you cannot conveniently read a newspaper by it, you can vaporise the newspaper which gives some satisfaction.

Having stressed the follies inherent in attempts to manage science, I should say that I do see a place for the funding of basic research on the grounds of perceived relevance. What I have been stressing is that, given the feeble range of human imagination, this procedure will not bring large returns, since it is not designed to produce surprising outcomes. And it is invariably the surprising outcomes that give one a lead that one can hope to sustain in a highly competitive marketplace. Drilling for oil in the neighbourhood of existing oil wells is a respectable occupation, but not one that creates new billionaires.

I have said more than enough about science policy. I close with some general reflections in regard to the impact of science on society.

The century that is past began with youthful optimism in regard to the benefits that would flow from science and technology. These high hopes have, to a great extent, been realized. Not only have we been wonderfully enriched on our lives by new understanding of the world we live in, but in addition we have benefited abundantly from modern technology.

It is easy, and foolish, to take these benefits for granted, while bewailing the fact that science has given us a new ability to do harm; harm to one another, and harm to the world we inhabit. Those dangers were apparent, in general terms, from the outset. The hazards, it is true, have proven to be greater than we dreamt. But so too have the benefits.

As I hinted at the outset, the most appalling of the negative effects of modern science were the pseudo-scientific movements that it engendered. This is not a comment on the dangers of science so much as on the dangers of ignorance of science.

The practitioners of 'scientific politics' divided themselves largely between communists and fascists. Both these utopian movements regarded the state as a machine, constructed according to optimal principles, functioning, as machines do, according to rules that are unchallengeable.

The philosophical underpinning's for this awful notion lay in a travesty of science. Science was conceived of as an infallible process, akin to revealed religion. The practitioners of this doctrinaire political science, since they were possessed of ultimate truth, felt no compunction in destroying their opponents, as did religious movements in days gone by.

Now, it is true that science does indeed have great authority. And it is also true that scientists are in pursuit of absolute, timeless, truth.

However, there is a world of difference between believing in the existence of absolute truth, and in believing that one can arrive at it. It is at this fateful philosophical cross-roads, as we should by now realise, that mankind chooses between slavery and freedom. For to believe in absolute knowledge as an achievable goal, is to provide a basis for absolute authority.

The reality of science is very different.

Science reveals a great deal, without at any time actually having proven anything, entirely beyond doubt. The power of science, as with any other exercise of human reason, stems instead from its ability to lead us toward the truth. It represents a process, rather than a destination.

By all means let us take science as a model for the structuring of society, but let it be science as it is. Not a body of knowledge, unchanging and unchallengeable, presided over by the high priest of the profession, but a society that, despite having an internal structure, is undergoing constant change.

The scientific community does have structure it has a priesthood. But it is an elected priesthood. It is recognised to be of paramount importance that those with authority be subject to challange.

This society of science is, then, an open one, embodying the warring elements of structure and renewal.

Science, which at the start of this century was taken to be the model for autocratic political systems, properly understood is the opposite: a model for democracy.

A great scientist, Lord Kelvin, was once asked what in his long career he regarded as most representative of his life in science. He thought briefly and then replied with the one word: "Failure". The process which is science is a stumbling journey out of ignorance into the misty landscape of truth.

Vaclav Havel, alumnus of long years in Czechoslavak jails and a thoughtful observer of the torments of our times, provided the essential text for what I am saying. He warned (in a book published last year):

"It is not hard to demonstrate that all the main threats confronting the world today ... have hidden deep within them a single root cause: the imperceptible transformation of what was originally a humble message into an arrogant one ..

Arrogantly, [man] began to think that as the possessor of reason he could completely understand his own history and could therefore plan a life of happiness for all, and that this even gave him the right ... to sweep from his path all those who did not agree to his plan".

["Open Letter" by Vaclav Havel; Vintage Books, N.Y. 1992 (p. 389)]

My final quotations on this vital topic come from the writings of Max Born. He issued a warning against those who use science to bolster their doctrinaire views. His message was, as you might expect, a subtle one, deeply rooted in his experience of science. He was the leading exponent of the statistical view of quantum theory, and in pondering this proposition he was led to issue a warning. It was a warning against a naive interpretation of Newtonian mechanics as providing a basis for a deterministic view of history the sort of view he had seen underlying the fanatical belief of the Nazis and of the Communists that history was forever on their side: Gott mit uns.

Speaking of this type of determinism, allegedly rooted in science, Born said the following ('Science and Politics', 1962, p. 34):

"Determinism presumes that the initial state is given with absolute precision. Given the smallest margin of uncertainty, there will be a point in the development of events from which prediction will become impossible. The concept of absolute precision of physical measurements is obviously absurd, a mental abstraction created by mathematicians ..."

The closing sentence of Born's Nobel lecture (1954) removes any doubt as to the moral that he wished us to draw from this:

"[For] the belief in a single truth, and in being the possessor thereof, is the root cause of all the evil in the world."

It is not easy to persuade an audience of scientists that philosophy matters. However, I think that this audience, all of whom recollect the evils perpetrated in this land by two successive autocratic regimes in the name of science, will not need to be persuaded. If science were a vast deterministic machine, there would be no hope for us. But since science is, in truth, a triumph of the imagination of many in a milieu that respects the spark of truth in each, there is every hope. It is within our power, little by little, to shape a decent and compassionate future. All the indications are that the Max Born Institute will take its place in that civilised tradition. I join with you in wishing it every success and long life.